Author: Hailey Kasney, Curations Intern

One of the greatest wonders—and oftentimes biggest challenge—of history are the documents that survive to tell it. What was the author thinking when putting ink to paper? Did they know their words would echo across time? Did they consider, in that moment, who might read their message?

In studying pre-Revolutionary North Carolina history this summer, I encountered many of these questions. The first sprang up in studying the Regulator Movement, a 1766–1771 farmers’ protest in what was then considered the backcountry of the colony. European-descended yeoman farmers—in increasing levels of unity and intensity—rose against colonial officials, demanding checks on government corruption, changes in voting practices, religious freedoms, and improvements in policies regarding land ownership in the backcountry. The farmers, who identified as Regulators, initially communicated their concerns through grassroots organizing and petitioning the colonial government.

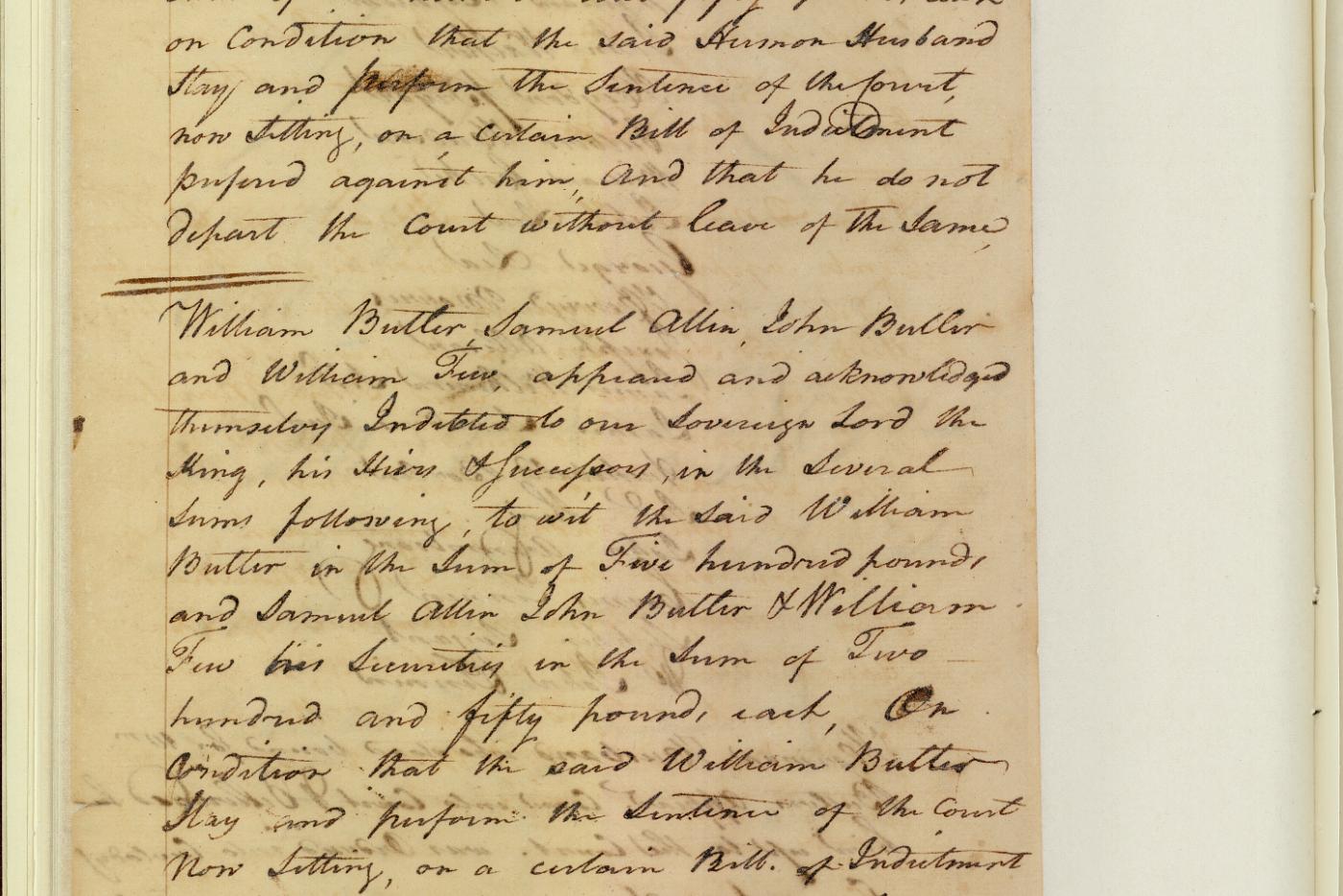

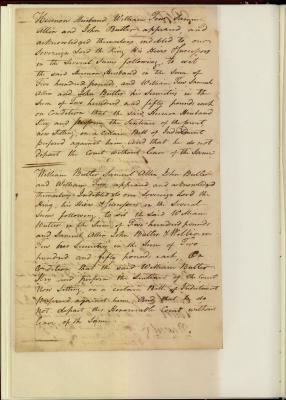

After years of unanswered petitions and rising tension between the Regulators and local officials, frustrations boiled over. At the 1770 meeting of the North Carolina Superior Court in Hillsborough, Regulators attacked local officials, running them out of the courthouse, and commandeering the court proceedings. Once the Regulator court was in session, they penned their own commentary into the court docket, creating what is known among historians as the “Regulator Docket.”

Alongside the standardized note-taking and fine script of the court officials, the Regulators made their thoughts known. Their notes appear darker on the page, more quickly written and perhaps with more pressure applied. It is easy to imagine the fervor and somewhat unsteady hands of the Regulators as they wrote themselves into the court proceedings that had long ignored and perpetuated their grievances. About some cases, they wrote the ruling was a “damn’d shame,” and of others, they disparaged local officials, in one instance writing that “All Harris's are Rogues.” This is a reference to David Harris, a supposed relative of Tyree Harris, who served as a sheriff in Orange County.

The Hillsborough Superior Court Docket was the Regulators’ way of marking their action in the record books. While some Regulator petitions and writings survive, much is still unknown about how they organized and the names of those involved. On May 16, 1771, the Regulator Movement was brought to a brutal end. A militia force of 1,000 men—led by North Carolina governor William Tryon—met 2,000 Regulators at a large field now known as Alamance Battleground. Upwards of 100 largely unarmed Regulators died under fire from the militia and the eight cannons they manned. Six more were hanged for treason, and Tryon’s forces razed Regulator farmland in the days following the conflict. In their final petition, the Regulators requested that the governor “lend an impartial Ear to our Petitions.”

As they faced armed forces made up of their fellow North Carolinians, the Regulators asked to be heard. Many of those lost to Tryon’s militia remain unnamed, and the Regulator demands dissipated with the fleeing and the dead. They sought dialogue and an accountable colonial government. Today, their words live on in their petitions, their final plea to be heard, and the dark ink of a hurried hand in the chaos of a courtroom.

Sources: