Author: Kimber Heinz, Charlie Knight, Tricia Williamson

The Horrors of War

Civil War wounds and injuries to arms and legs were often so severe that doctors had no choice but to amputate. Thousands of soldiers received this treatment, usually the safest available. In January 1866, North Carolina became the first state of the former Confederacy to provide veterans with prosthetic limbs.

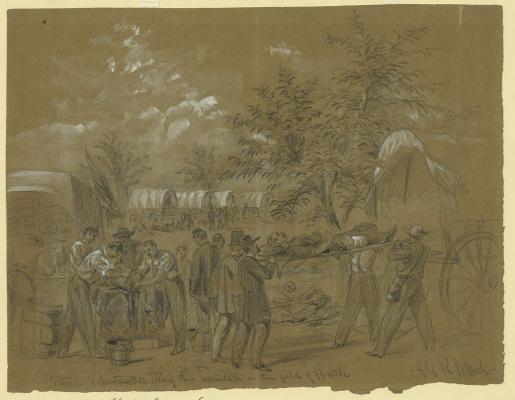

A Civil War battlefield was a terrifying place, but the horrors of a field hospital could be much worse for those wounded while fighting. “The days after the battle are a thousand times worse than the day of the battle,” wrote Maj. William Child, surgeon of the Fifth New Hampshire Infantry, several days after the Battle of Antietam. “The poor wounded mutilated soldiers that yet have life and sensation make a most horrid picture.”

Surgeons, some of them poorly trained, moved in rapid succession from patient to patient. For some of the wounded soldiers, nothing could be done for them. For others, their wounds were stitched back up. If they were lucky, the surgeon might have wiped the blood from the previous patients off his tools. The very lucky soldier might get a clean, unused bandage. For others, bullets or artillery fire might have shattered an arm or a leg. For them, the only treatment usually was amputation—the removal of the limb.

The first limb-amputation surgery of the Civil War is thought to have been performed on Private James Hanger of what became the 14th Virginia Cavalry. When Union forces attacked his camp on June 2, 1861, a six-pound solid shot ricocheted off the ground and struck him in the leg.

After being held prisoner for several months, Hanger was sent home with what in essence was a peg leg. It was ill-fitting and difficult to walk on, so he devised his own prosthetic leg that featured articulated joints at the knee and ankle. Hanger went on to patent his prosthesis and developed one of the largest manufacturers of prosthetic limbs in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The company still exists today.

Help for Veterans in Post-War America

More than three million soldiers served in the Union and Confederate armies during the war. Around 475,000 were wounded in battle, with about 60,000 losing limbs to amputation. For many of those amputees, the loss of an arm or leg may have meant the loss of their livelihood, especially if they were skilled laborers or farmers, in addition to the immeasurable psychological aspects.

Beginning in 1862, the US government began issuing payments to amputee Union soldiers to purchase prosthetic limbs. With the collapse of the Confederacy in 1865, no such assistance existed for former Confederate soldiers. In 1866 the North Carolina General Assembly passed a resolution to provide artificial limbs to those soldiers who lost an arm or leg in the state’s service. The state contracted with Jewett’s Patent Leg Company of Washington, DC, to set up a factory in Raleigh near the Raleigh & Gaston Railroad. North Carolina was the first former Confederate state to take such action for its veterans.

It is not known exactly how many North Carolina soldiers lost limbs during the war. Approximately 1,550 North Carolina veterans reached out to the state for either a limb or for financial assistance during the program’s five-year existence.

The large volume of veterans with amputations and injuries had impacts long after the war ended. The Civil War was a catalyst for the growth of American medical science. About three-quarters of the surgeries performed during the war were amputations. Doctors and surgeons practicing during and after the war were able to advance their medical knowledge, using what they learned from the battlefield.

Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, compiled by the Surgeon General’s office of the US Army, is one example of the knowledge that came out of the war. The multivolume compilation included medical insights from Confederate and Union doctors.

Impact on Modern Society

The connection between the history of the Civil War and disability history is just starting to take shape. Historians and the wider public have tended to see disability as biological instead of something shaped by history and culture. That view is changing thanks to the work of the disability rights and justice movements.

Historians are starting to see disability itself as a historical category, in terms of causation (e.g., a war injury), how disabled people experience the world, and how society defines and responds to disability. As historian Douglas Baynton wrote, “Disability is everywhere in history, once you begin looking for it, but conspicuously absent in the histories we write.”

A disability history approach focuses on the experiences of disabled veterans. Providing prosthetics was no doubt a service to many, but others may have viewed it more negatively. Health insurance and accommodations didn’t exist during this time, and there were very few social welfare programs. As a result, disabled veterans may have felt the pressure to "overcome" their disability to support themselves and their families.

One 1866 editorial in the North Carolina Standard newspaper claimed that “legs ‘make the man almost over again’ and allowed him to become a ‘producer’ rather than a ‘consumer.’” Some men received prosthetics but never used them. Others simply preferred to receive money from the State.

Was the Program a Success?

For those who received Jewett limbs, the reviews were mixed. Sergeant John L. Cathey, 60th NC Infantry Regiment, who lost a leg at the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, complained that while the leg given to him fit when he first tried it on at the shop in Raleigh, he found it completely unsuited for use outside at his home in Asheville. “I have worn it one time and since that time I cannot get my leg in it to try it anymore.” Others liked their state-provided prostheses so much that they wore them out and needed replacements.

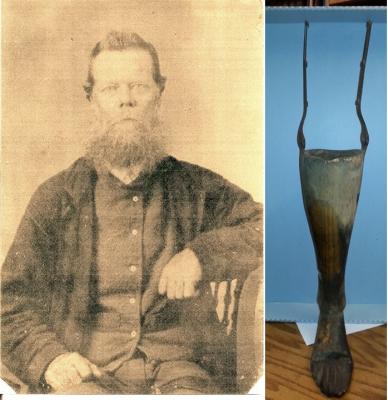

Corporal Spencer O’Brien, 23rd NC Infantry Regiment, lost a leg at the Battle of Cedar Creek in October 1864. O’Brien filed a claim and received a Jewett leg in July 1866. He either preferred the one he made himself or the Jewett leg wore out, because photographs from later in life show him using a leg made from a wagon axle. The NC Museum of History has O’Brien’s wagon axle leg, as well as several prosthetic legs used by Civil War veterans.

The Jewett limb factory in Raleigh closed on June 18, 1867. The plant closed due to a lack of business, but the state’s program remained active and dedicated to providing limbs to veterans until 1871. Other states, like Virginia, used the success of the program as a foundation to help their own disabled veterans. Few of the state-issued Jewett limbs survive today, either from wearing out or being disposed of after the soldier’s death. You can see a Jewett limb currently on exhibit at Fort Fisher State Historic Site.

Bibliography

Baynton, Douglas. “Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History.” in The New Disability History: American Perspectives, edited by Paul K. Longmore and Lauri Umansky. New York University Press, 2001.

Handley-Cousins, Sarah, Jenifer L. Barclay, Moyra Williams Eaton, Jean Franzino, Allison M. Johnson, and Fred Pelka. “Disability in the Civil War Era.” The Journal of the Civil War Era 14, no. 2 (2024): 194–224.

National Park Service. “Antietam: Letters and Diaries of Soldiers and Civilians.” Updated January 11, 2024.

Wegner, Ansley Herring. Phantom Pain: North Carolina’s Artificial Limbs Program for Confederate Veterans. NC Office of Archives and History, 2004.